Tulane School of Architecture Outstanding Undergraduate Thesis Award Recipient, 2024 aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa research & design team: Fiona Alicandri & William Trotteraaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa all works featured on this page authored by William Trotter

With a surplus of vacant office space as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, research indicates conversion efforts solely prioritize residential remodels. Considering the pitfalls related to the cost (both in construction and user expense) and spatial quality of these conversions, this model argues that there are additional programmatic arrangements and opportunities not being explored for these vacant spaces.

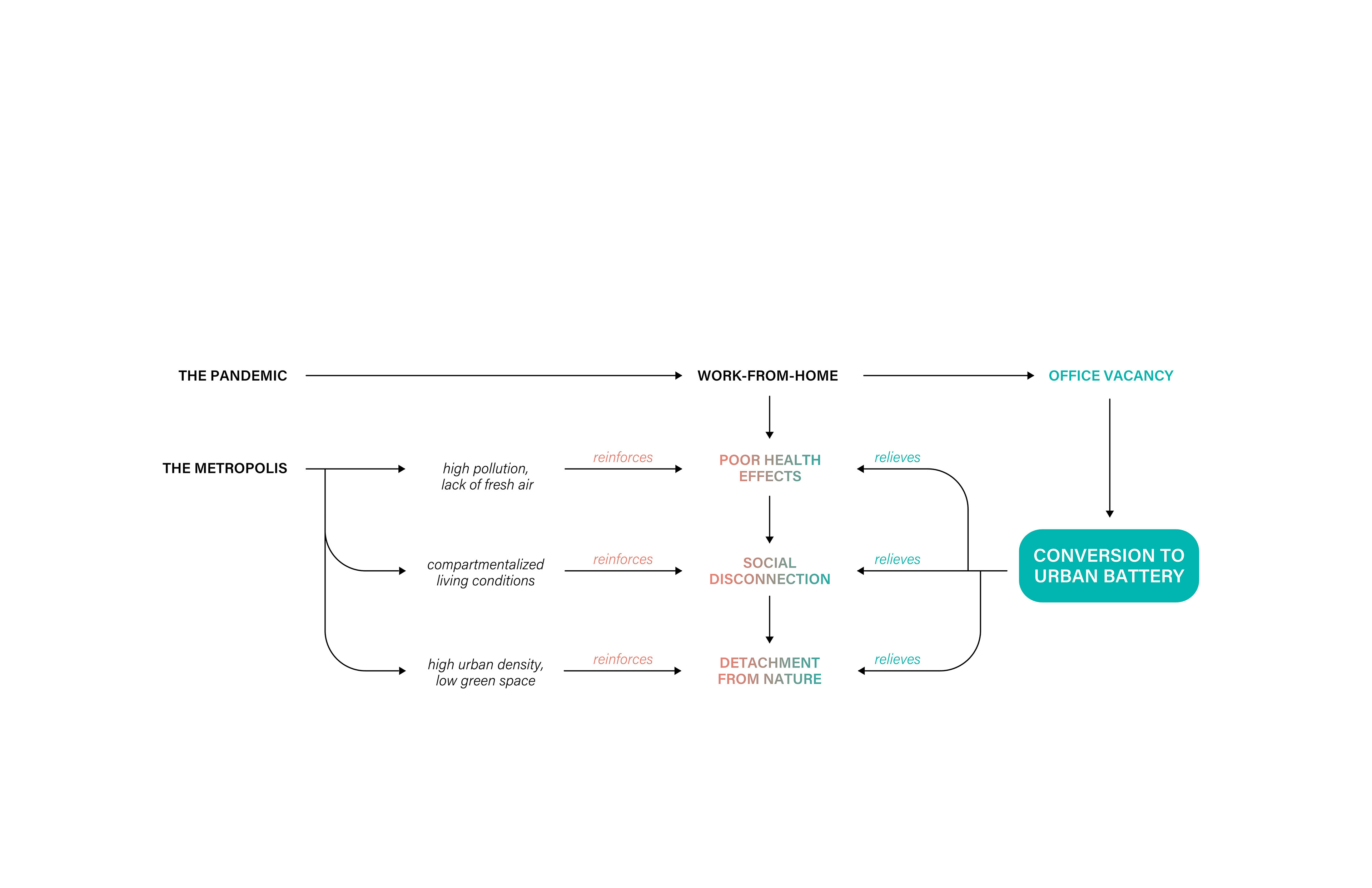

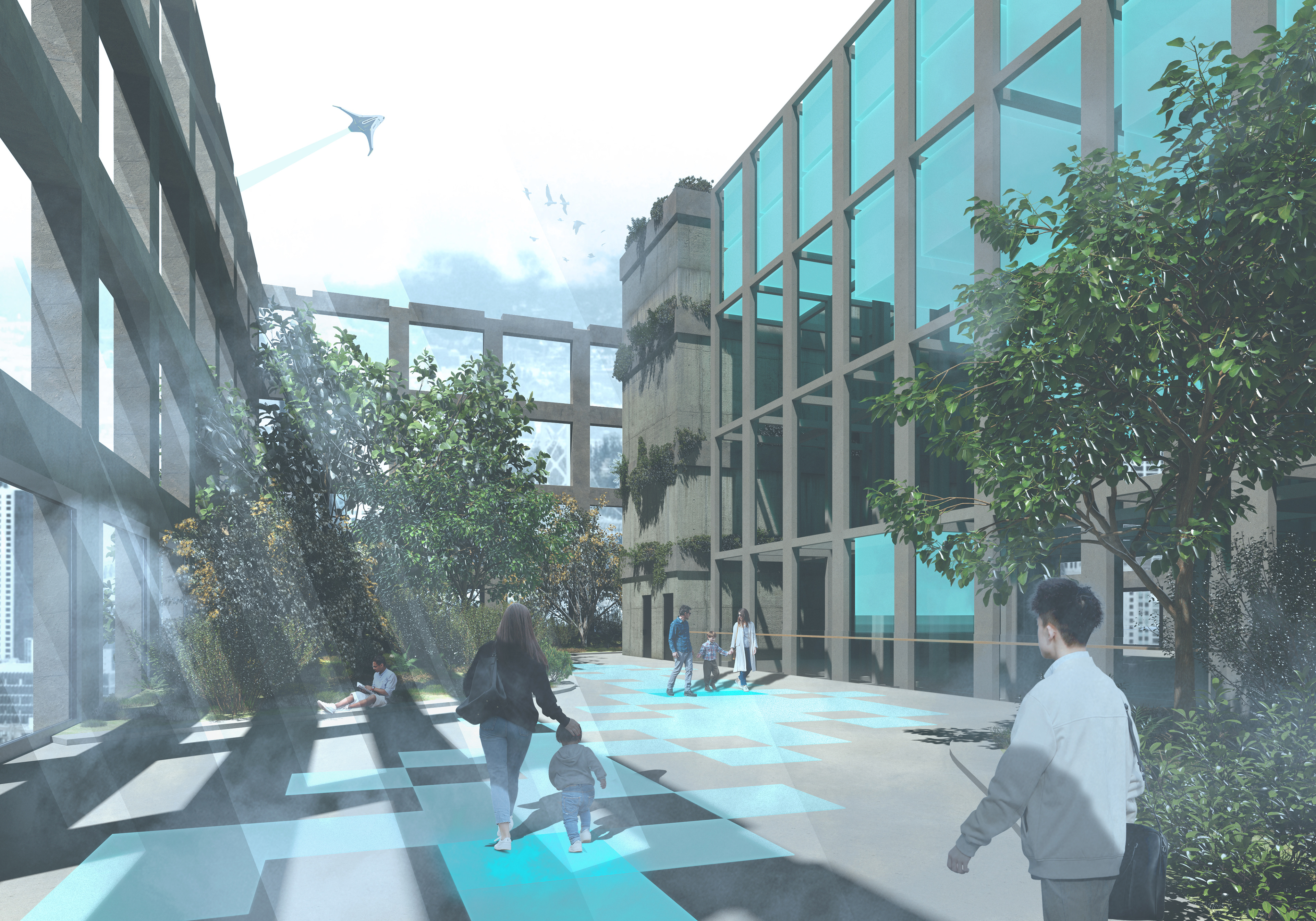

Offering a reciprocal solution to these new voids in the urban fabric, Noosphere II proposes transforming vacant office towers into ‘urban batteries’ that recharge the social and ecological deficiencies of the metropolitan condition through hubs of transportation, socialization, and environment.

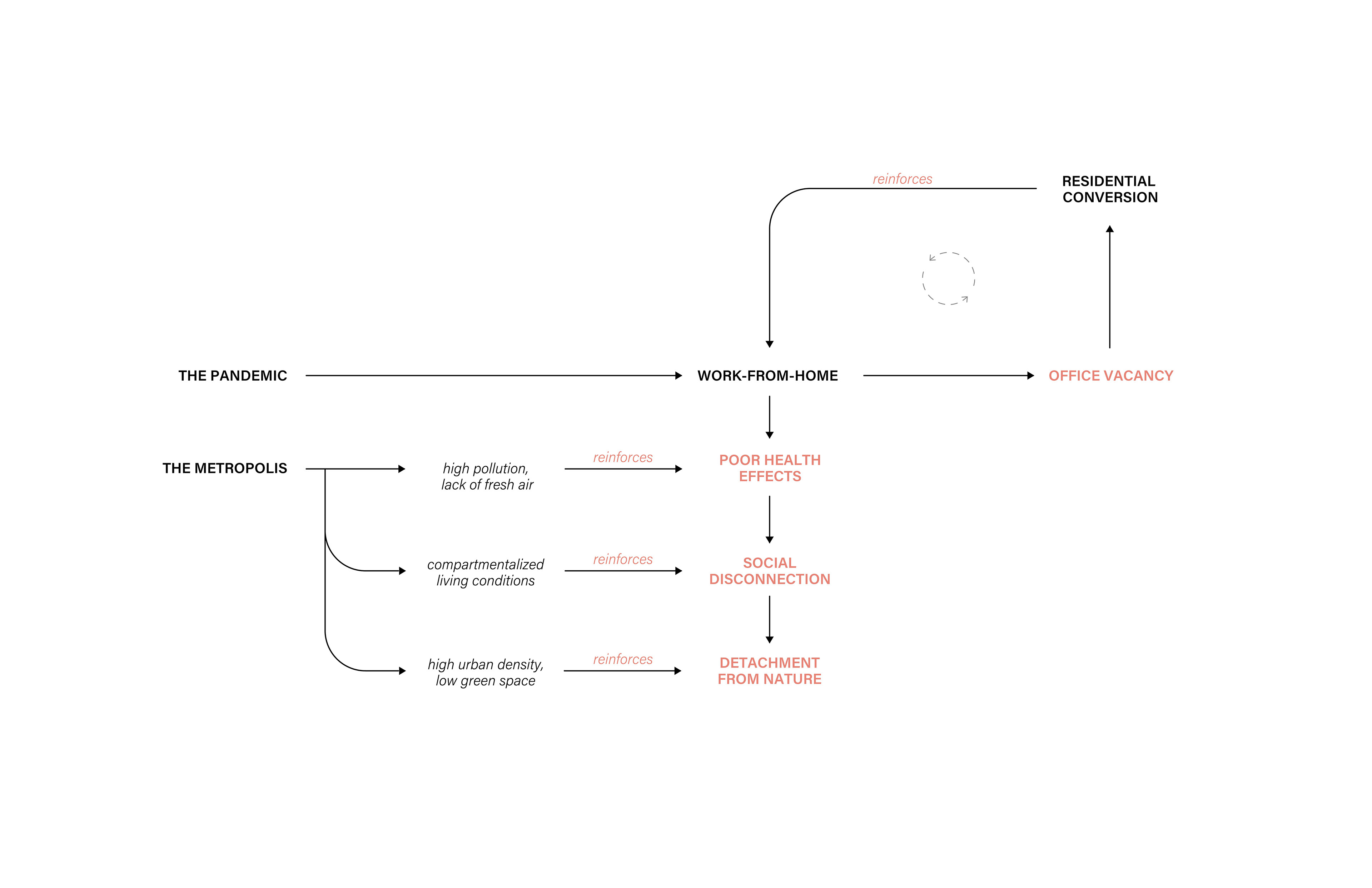

Research indicates that those who work solely from home are experiencing an increase of physical and mental health complications. These complications are often compounded by the living conditions of those who work under this model, as dense metropolises were the most affected by the pandemic and therefore contain both the largest work-from-home workforce and highest office vacancy. Overcrowding, pollution, and lack of green space typical of these cities each add to the social and physical detriment of the metropolitan occupant.

Though four years out from the pandemic, cities in the U.S. have largely stuck with this work-from-home system, leaving commercial office spaces vacant with no consistent trend to indicate a potential full return of the workforce to these buildings. Cities across the country and around the world are proposing converting these spaces into housing, although several complications arise from this.

current model for the at-home worker

proposed model for the at-home worker

The current model for the at-home worker in the modern metropolis shows what forces are presently at play. Subsequent office vacancies and attempts to convert these for residential use create a feedback loop that deprioritizes office space and increases compartmentalized, anti-social housing.

To alleviate these conditions, this proposed model converts vacant office buildings into urban batteries that counteract the compounding effects of the metropolis on the occupant, thereby aiding those that unintentionally contributed to the abandonment of these spaces in the first place. Its ultimate objective is to establish a new urban program that injects social, environmental, and urban infrastructures into dense yet socially and ecologically isolated areas.

The ecological score chart above uses empirical data concerning vacancy, density, and ecological conditions of major US metropolises in each region to help establish a city and site for investigation. San Francisco's Union Square District reflected the most severe score and was therefore selected as the initial testing grounds for this proposed model.

Though human technology continues to cause irreversible damage to our global ecology, a future can be envisioned where it is exclusively harnessed to foster reciprocal relationships with nature-- especially in dense urban settings where natural and social connectivity are lacking, and large-scale building vacancy is at an all-time high. The research led to implementing the Noosphere, a philosophical concept constructed through conversations between Soviet mineralogist Vladimir Vernadsky and French theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in the late 1800s (diagrammed above). We argue that employing a socially and ecologically oriented architecture that emphasizes a union of nature and human technology within these vacant spaces would encapsulate and celebrate the same principles put forth by Vernadsky and De Chardin, thus physically embodying the Noosphere.

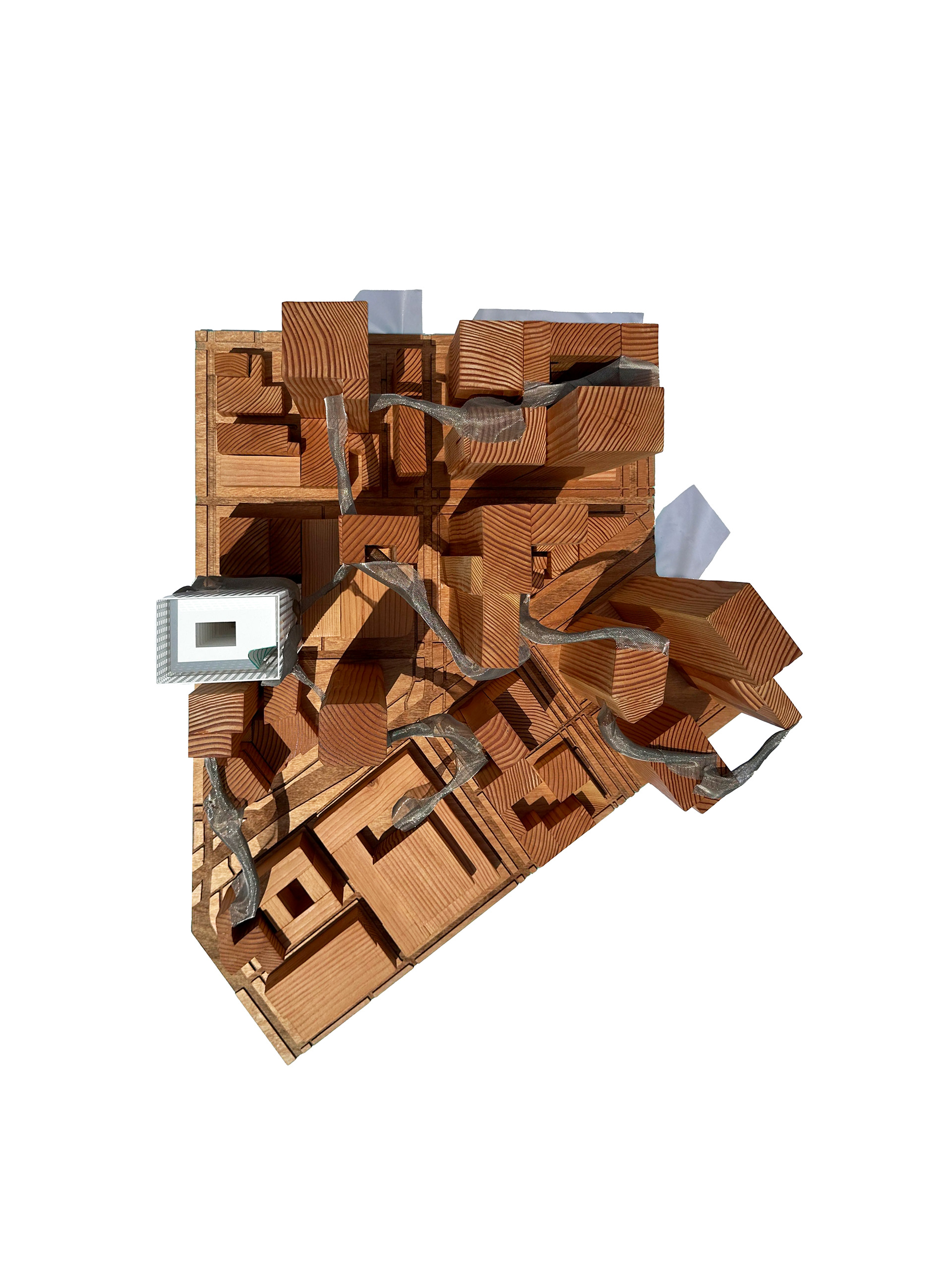

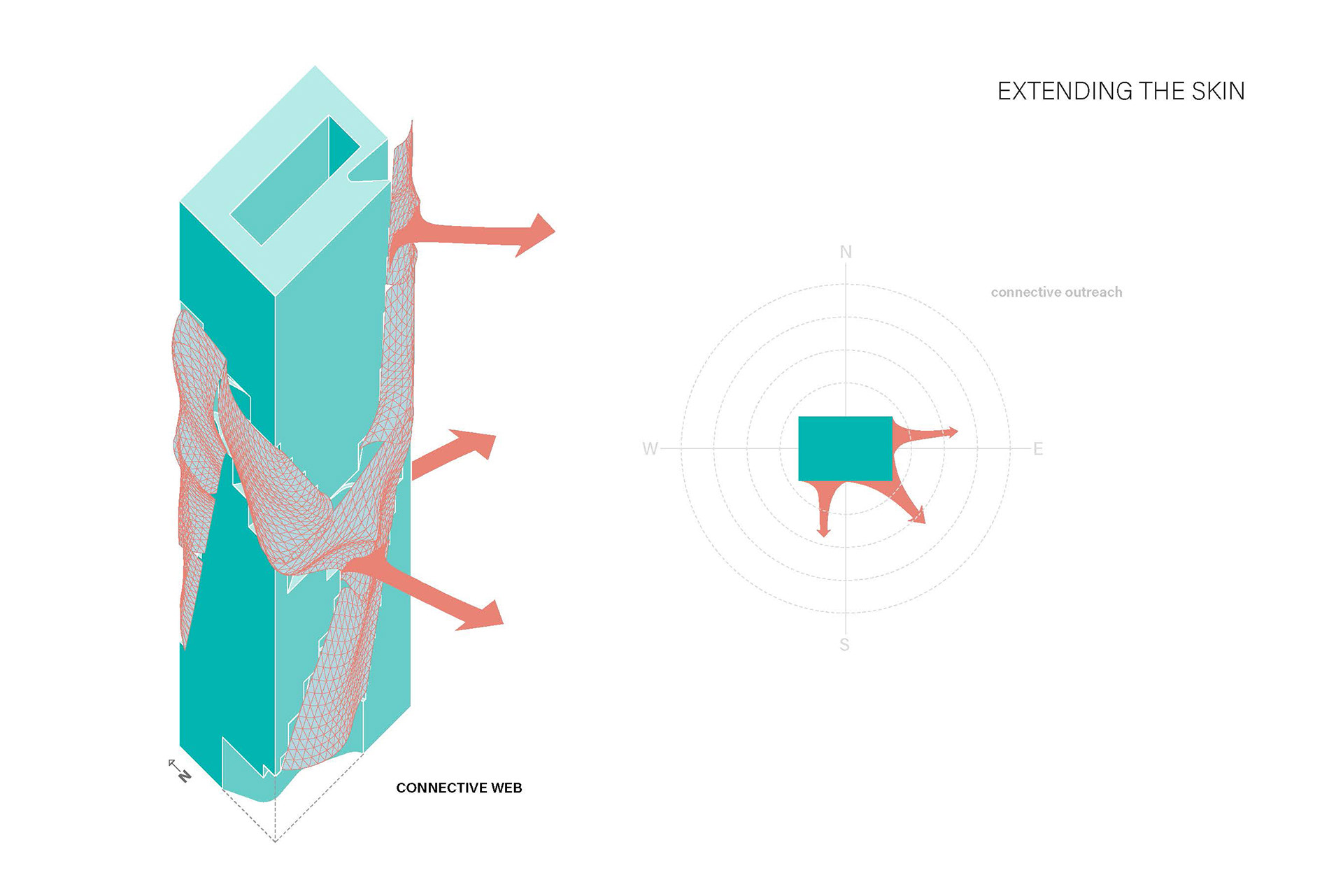

It was through an exploration of the three dimensional qualities of the context that the research began to denote ways for Noosphere II to operate outside the bounds of its walls.

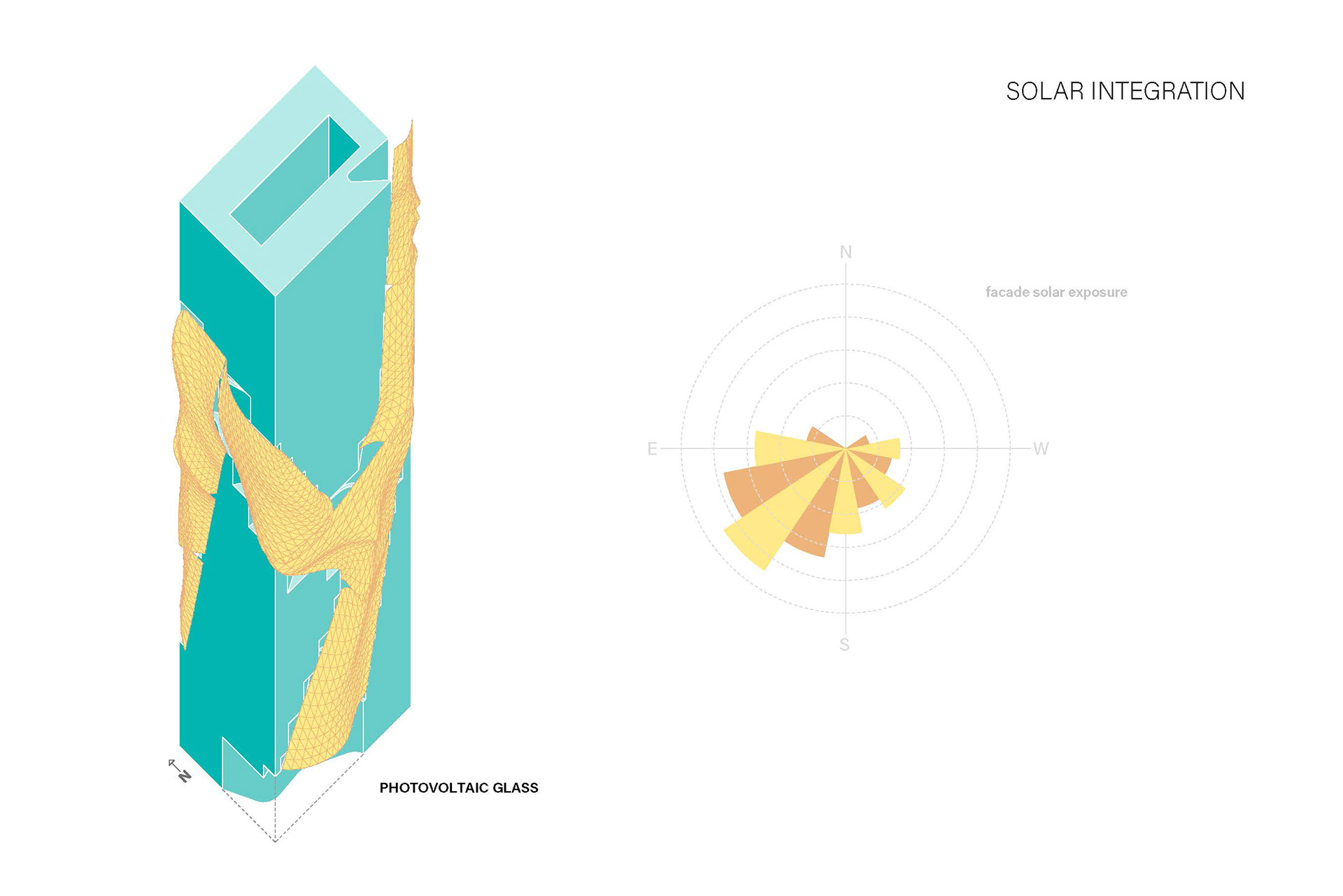

We investigated the opportunity for a solar façade network to be implemented on the surrounding blocks, as nearby towers sit on the edge of a low rise district and receive ample sunlight (see the diagrammed model above). In thinking about the building as a hub of social and literal energy, physical connections to these spaces can form above the ground plane.

This ideation of multi-block connections culminated in the establishment of a microgrid model, where the building acts as an energy generator, battery, and distributor for its direct context. As shown in the abstracted diagram below, this severs participating buildings’ connections from the city grid, instead creating an island of clean energy within the metropolis.

1:500 site model with future connections

1:500 site model with future connections

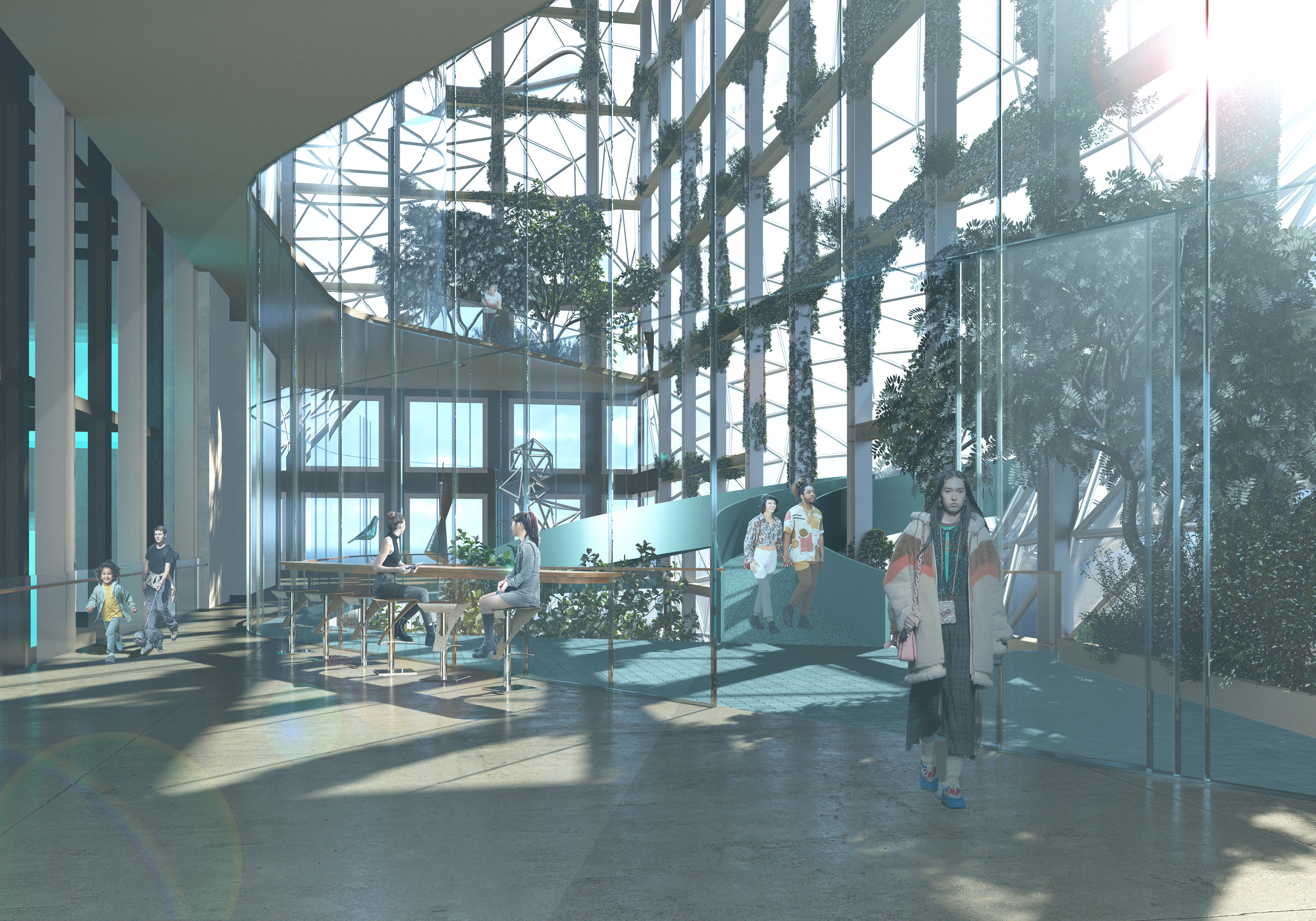

The building's role as a green energy hub is physically manifested both internally and externally to allow the public to inspect and interact with its components. The structure incorporates several emerging technologies in grid storage (analyzed and compared in this paper) including the gravity battery, a series of turbine-bound weights and shafts that store excess electricity as potential energy (learn more here).

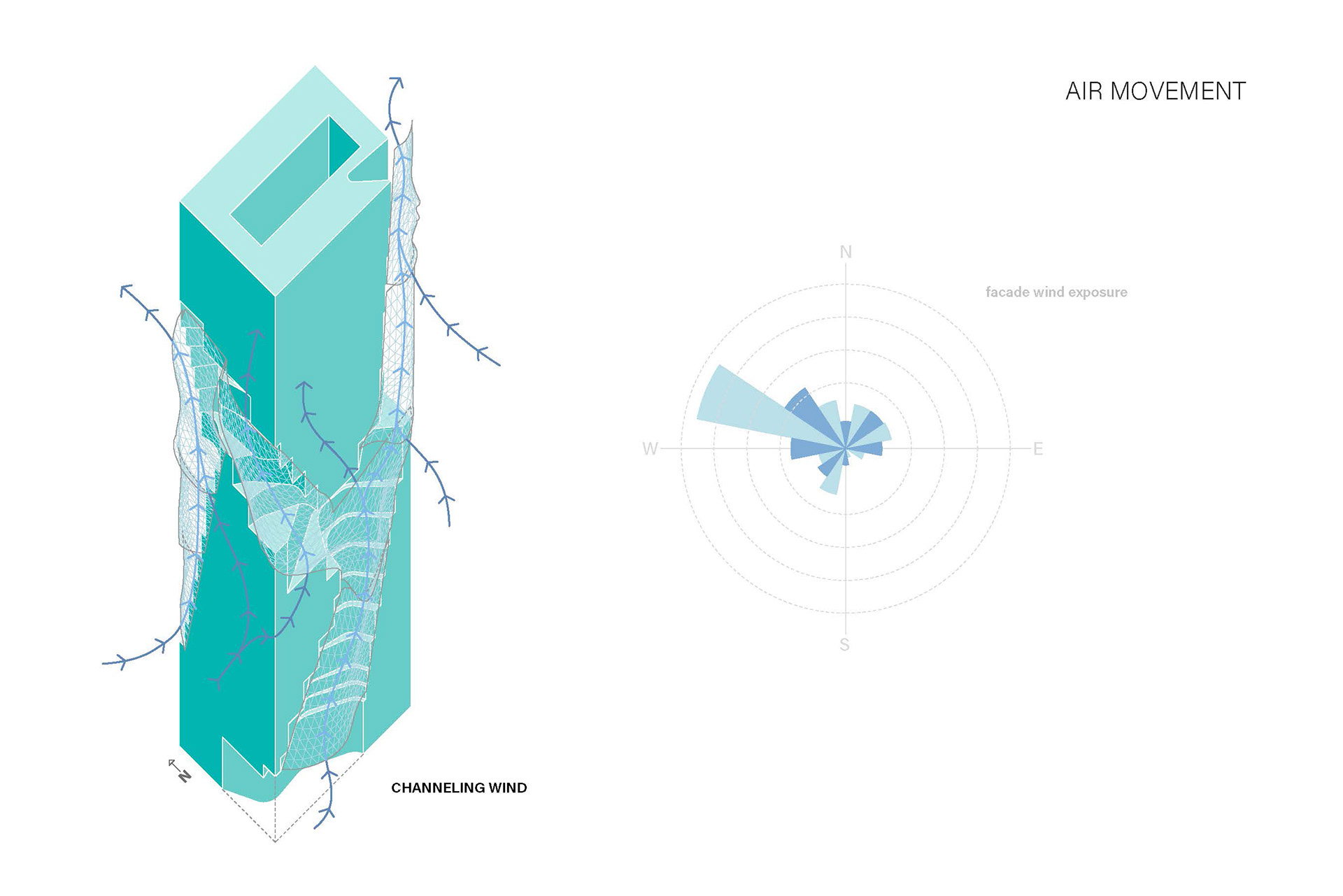

The building's external skin is a hybridized physical manifestation of the solar and wind capture opportunities for the site, where photovoltaic glass produces energy and air moving around the building is brought within to ventilate green spaces. The façade's organic form also establishes a language for the elevated pedestrian network to play with, as "ecological inserts" connect vacant portions of neighboring towers.

Programmed as a hub of science, art, culture, and nature with a renewables-supplied gravity battery running through its core, Noosphere II provokes an untested merger of community program and ecologically-oriented infrastructure. In establishing a multi-block sustainable microgrid, a vertical park, a transit hub, and physical connections to its direct context, the model reintroduces nature to the places humankind needs it most.

connection level

AR experience hub

rooftop ecotechnic museum

1:250 sectional model

1:250 sectional model

1:250 sectional model

1:250 sectional model

1:250 sectional model

Post Montgomery Tower, 2024

Post Montgomery Tower, 2044

Post Montgomery Tower, 2024